“Be the Moon (that’s what a woman said to her son at his funeral)” What remains when maps fail? Perhaps looking from the Moon. Artist Lucas Canavarro revisits the work of Emilia Estrada and her exhibition Drawings of Arrival, curated by Ana Clara Simões Lopes, where the Moon appears as refuge, archive, and vanishing point from which to think about land, borders, and a war that never ends.

It is July 2023. I am saying goodbye to Jerusalem. I am on my way to the Tel Aviv airport while talking with Luai, a taxi driver and travel companion. Born in Palestine and holding a document that allows him to have an Israeli passport, he tells me, throughout our one-hour journey, the stories of his travels around the world. He highlights his experiences in Asia and Africa, but regrets his time in Latin America, when he spent two months in Guatemala. The neighbors of the house he rented, he says, were constantly warning him about the violence in the streets. That made him nervous. “I was born and raised in war, but I don’t know how you can live like this.” Next, Luai tells me about the geological formation of Palestine, starting with the time of Pangaea. He begins by explaining that the Mediterranean, the Sea of Galilee, and the Dead Sea are direct descendants of the Tethys Sea, a Mesozoic formation also known as the Sea of the Tongue, due to its shape. That's when we were stopped at an Israeli checkpoint. They asked for our passports. We remained silent.

Luai owns a haie el zarqa [الهوية الزرقاء], one of the various types of documents that a Palestinian can obtain under the colonial rule of Israel. Having this general record, he must present it as a kind of passport, within his own country, in order to be able to move between the borders that fragment his land —the only city he is not allowed to enter is Gaza. This identity document is also the only one among the local records that allows a Palestinian to obtain a passport —an Israeli one, in this case. His name appears in that passport, but not the name of his country of origin. This is how Luai can travel the world. After a few questions, they returned our documents to us. We continued the journey. Luai's tongue fell silent. This taxi ride is one of the memories that come to mind as I write about the work of Emilia Estrada.

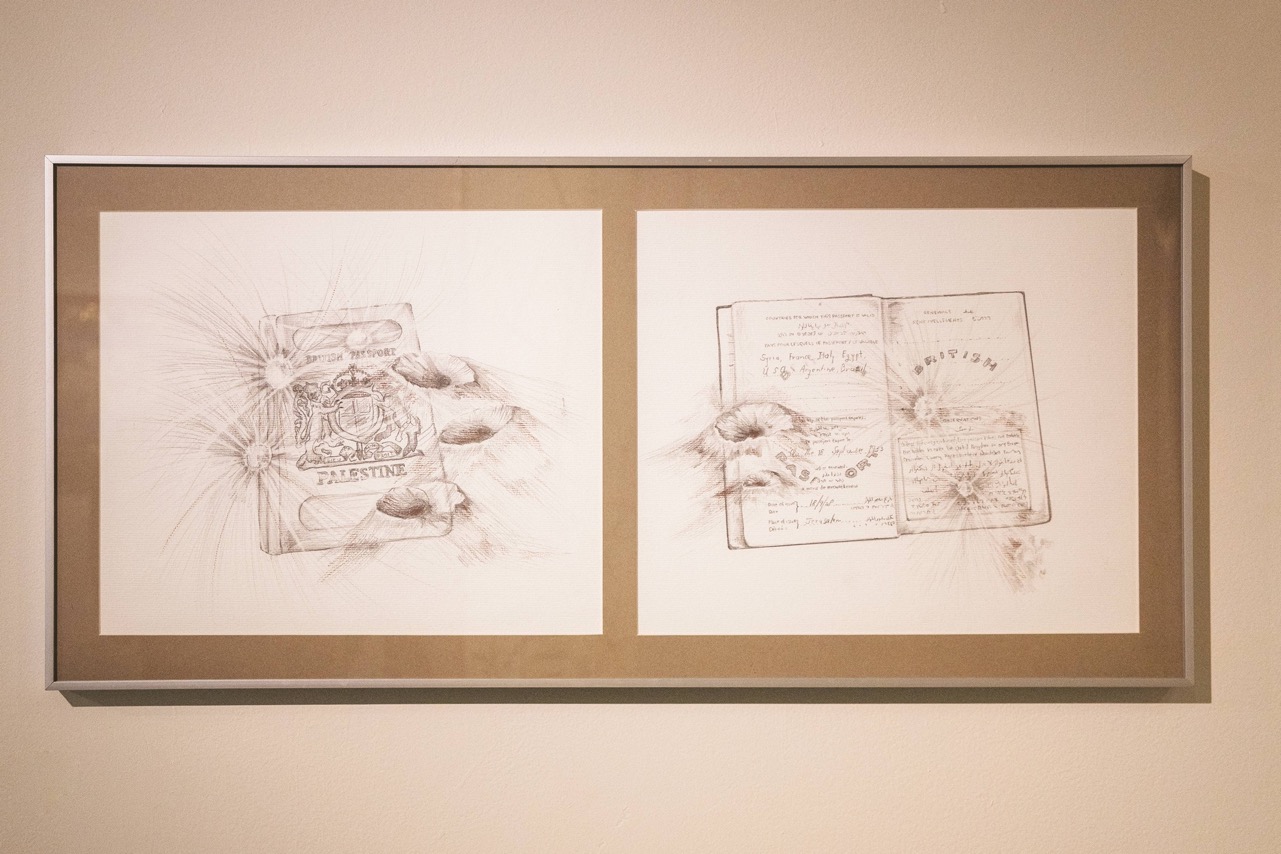

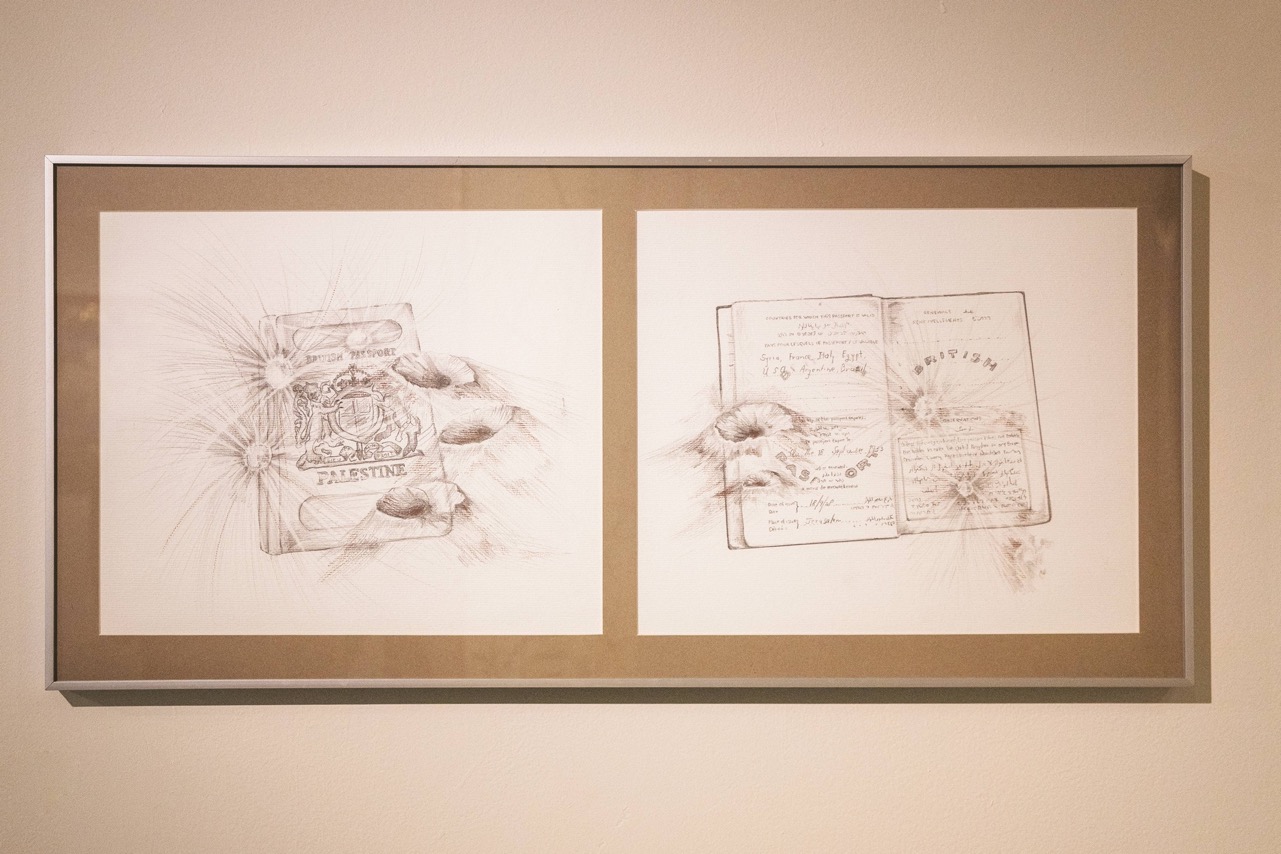

At the center of her first solo exhibition in Rio de Janeiro, “Dibujos de llegada” [Arrival Drawings], curated by Ana Clara Simões Lopes at Sesc Ramos, a drawing imagines the existence of a British Mandate passport in Palestine, which belonged to her grandmother, wrapped in silhouettes of lunar craters. That phantom document reminds us that, of the millions of Palestinians in the world (an imprecise figure), half are in foreign territory.

Granddaughter of that diaspora, the artist traces her trajectory in the visual arts through an open thinking about names, documents, maps and territories. Born in the Argentine city of Cordoba, Emilia is of Palestinian descent and has resided in Rio de Janeiro since 2014. The Palestinian musical collective 47Soul, singing in English, is now making its presence felt: “I don't care where you're from.”

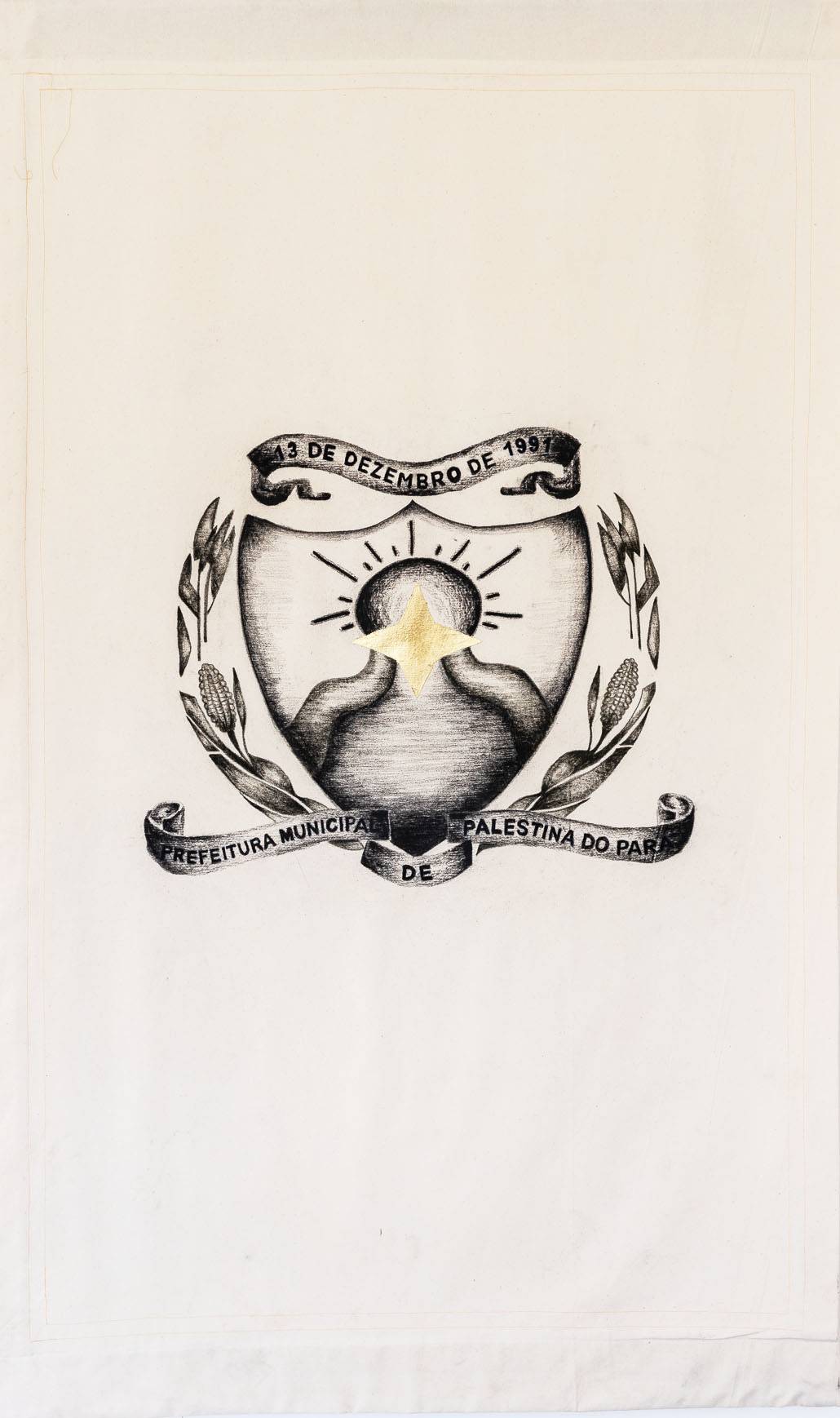

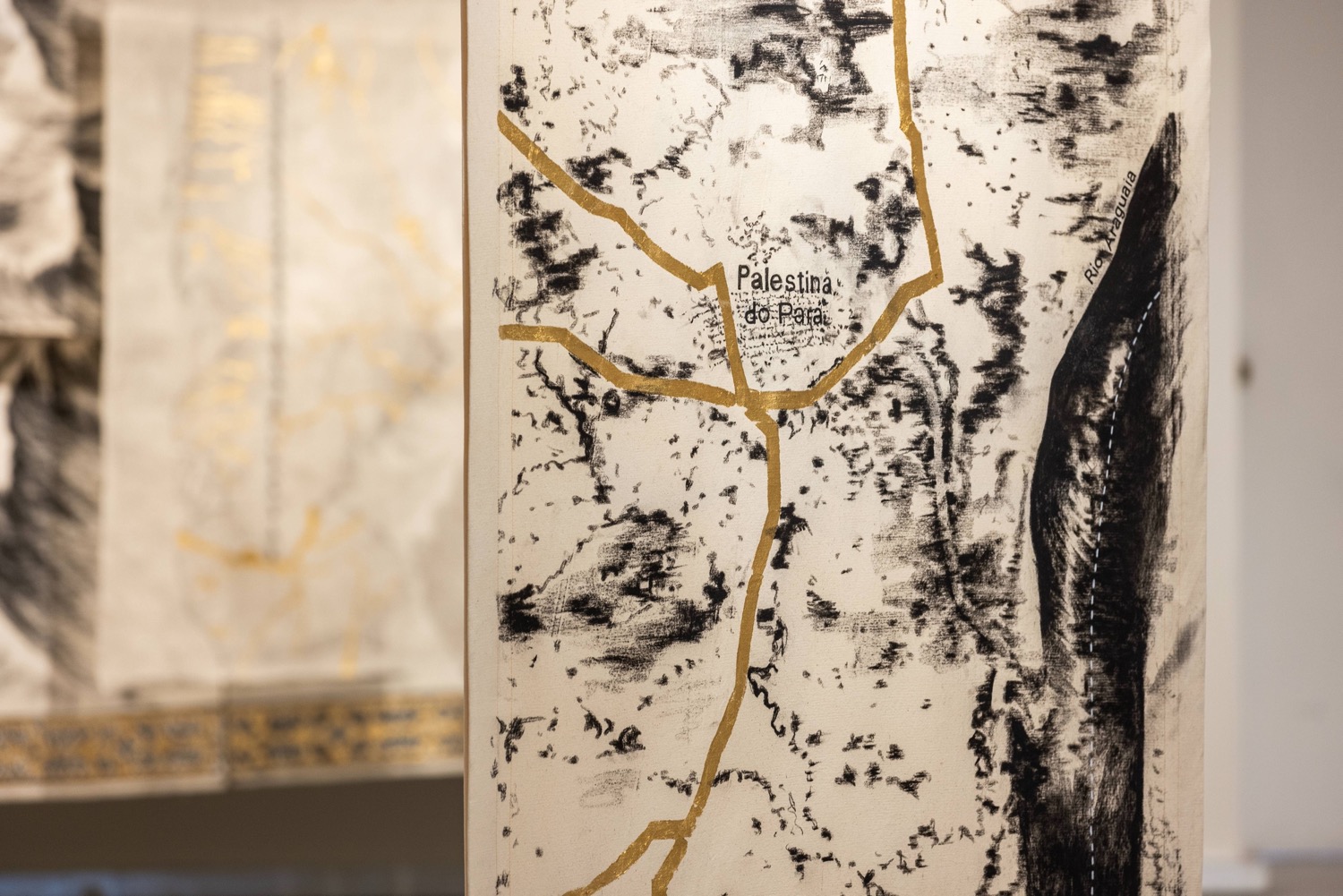

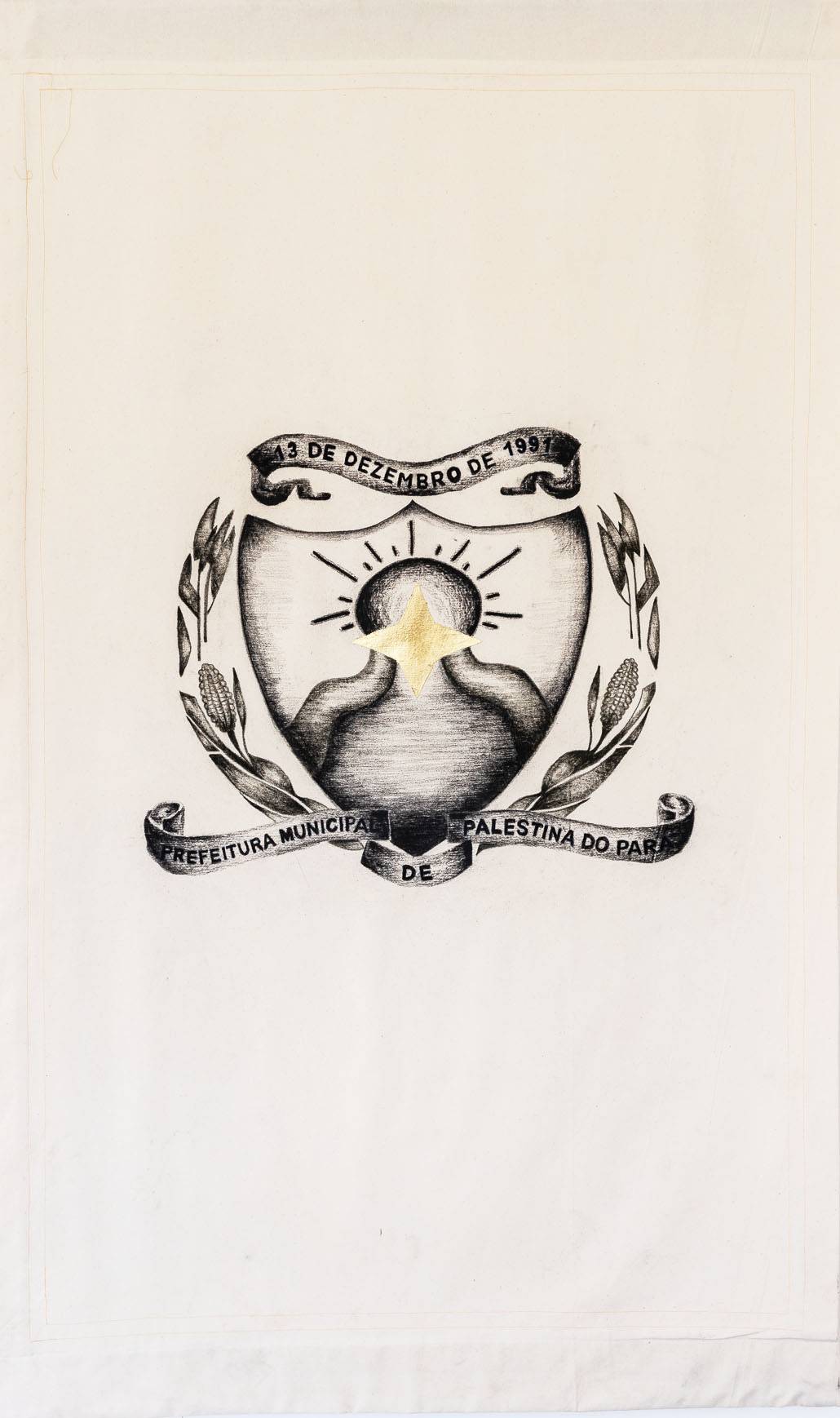

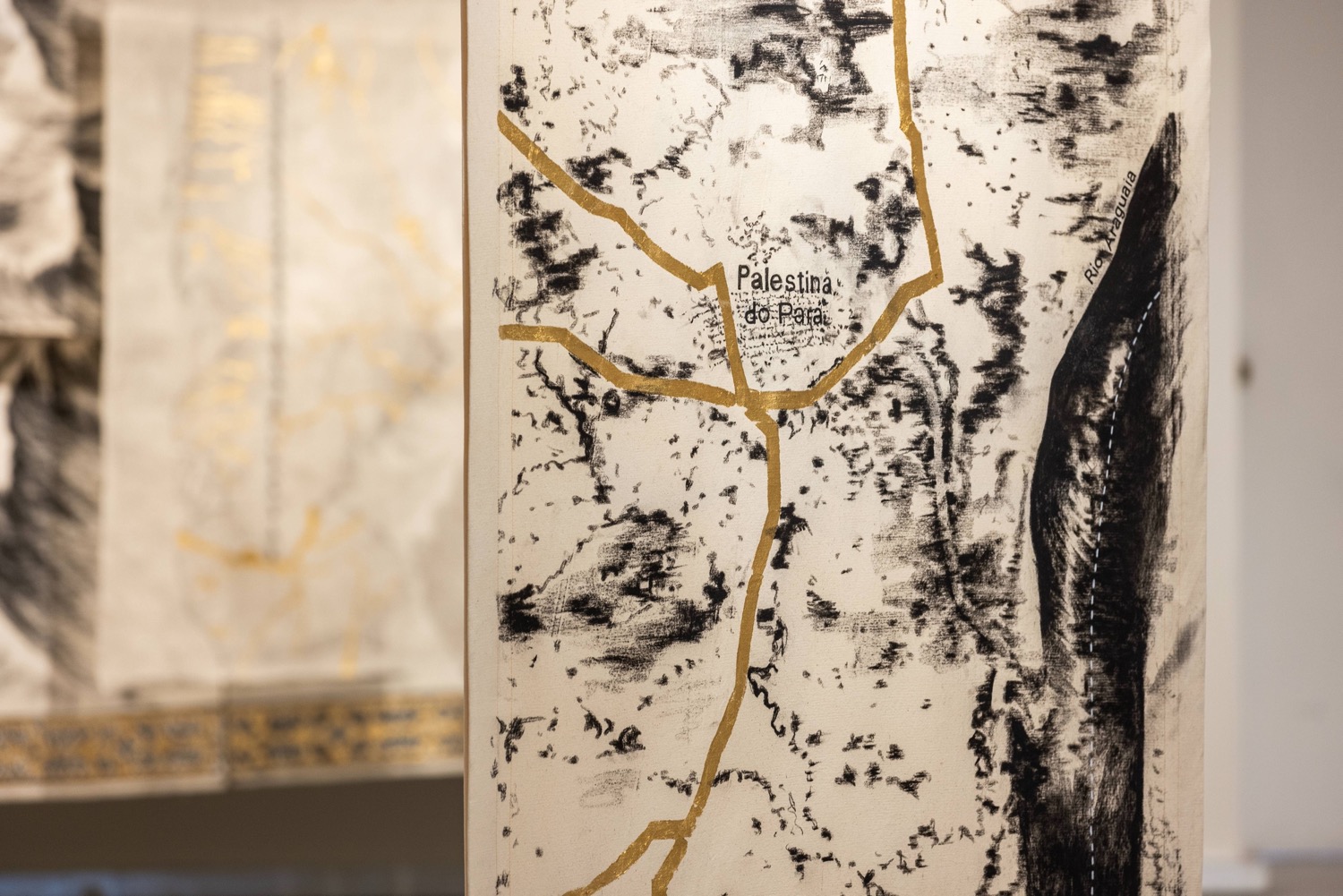

Emilia's transfrontier nature belongs to places marked by land conflicts, all of them related in their wars, all of them continuous nakbas [النكبة], occurring in different timelines of the same coloniality. It is no coincidence that Donald Trump announces a peace agreement in Gaza the same week he bombs ships in the Caribbean Sea. Palestine is not the world. The world is indeed a Palestine with many Gazas, general laboratories of the vulgarization of death. And so, the artist displays nominations: of Latin American cities called Palestine; of fragments of land on the Moon with the names of Arab astronomers from Al-Andalus; of the farces of union and fidelity in the Praça Tiradentes in the center of Rio —which, despite its name, holds in its center an immense statue of Dom Pedro I, carried by indigenous people from different regions of Brazil.

It is December 25, 2024. I spend Christmas at Emilia's house in Rio. On the table there is coffee and halawi [حلاوي] that she herself brought from Ramallah. In the last eighteen months, we have been in Palestine at different times —historic times, even, with an October 7th in the middle. Sharing our experiences with that land is a strange force that unites us. In our sort of fraternal Christmas dinner, we tell stories and try to connect some dots on a global board of conflicts. Brazil remains entangled with the monstrous Temporary Framework Bill, which keeps returning with different cynical faces. Its clear inspiration is the Palestinian Nakba. In his work Carta al viejo mundo [Letter to the Old World], Jaider Esbell writes on one of his paintings: “There is genocide in the Amazon rainforest.” Doesn't the (old) world know? But isn't the world itself a Palestine? The world sees the genocide in Gaza, and? In Salvador, in Bahia —where I live—, there is a periphery called Palestine. From there, Timbalada sings that "Jesus, since childhood, is Palestinian," which could very well mean that Jesus is from Bahia. On this emblematic date, Emilia observes the Moon with a magnifying glass. Maybe she's looking for her grandmother.

While the lights of that December were going out, I had been working on the installation of Louvor à Sombra [Praise to the shadow], present in the exhibition “Forma das Aguas [The shape of water]”, at the Museu de Arte Moderna de Rio, curated by Pablo Lafuente and Raquel Barreto. The lunar surface seems to have become a kind of refuge from which the artist can once again contemplate the blue. A displacement made of coal and gold leaves, to put some colonial concepts on the coffee table, to put them in dialogue, to expose them. What is a territory compared to the power of an Earth? Are there territories on the Moon? Or is the Moon itself a territory? In that case, would the Moon be a moonatory? Emilia observes from the sky. The Palestinian poet Mahmud Darwish writes: “In the dream of the loved one, be the Moon (this is what a woman said to her son at his funeral)”. That night I dream about my grandmother.

That same Moon manifests its profound influence in Dibujos de llegada [Arrival Drawings]. In the work Rumores aridos en rumbos humedos [Arid Rumors in Humid Courses], Emilia seems to create a counter-plane of the Moon and contemplates the surface of the ocean portrayed in the archives of European colonial navigation. The tides are transformed into a mapping, made with a kind of telescope installed on the lunar surface. The artist transforms her gaze into a prayer about the influence of water on a reality that is under a process of transformation. This map of a tide overlaps with that of the City of the Caesars, a mythical city in Patagonia that could never be invaded by the conquerors thanks to the resistance of its original owners. Like the Amazonian Eldorado, the impossibility of mapping it —because it is in another dimension— makes it precisely a point of interest for Emilia.This interplay of opacities and transparencies returns in the series Observação à sombra alta [Observation in the high shadow], in which the artist highlights lunar craters whose Arabic names were given by Western scientists. The names seem to want to give a face, a personality, to those fragments of land. If they had a passport, their name would be printed on it, but not their place of origin. Passports say very little about who their owners really are.

In his essay “The destruction of Palestine is the destruction of the planet”, Andreas Malm recounts the strategies of the British Empire in the 1840s to construct the idea that Palestine was “a land without a people”, “a fertile country, nine-tenths of which lie desolate”. These are accounts taken from diplomatic documents of the time, which reveal the long and slow process of hypnosis that founded Zionism in the region, culminating in the Nakba, more than one hundred years later. When I went to Palestine I found a truly fertile, abundant, and rich land. With cutting-edge research, LGBTQIA+ people, and women in leadership positions. With numerous artists, universities, thinkers, cultural centers, and culture makers. Not by chance, a sacred land also inhabited by many invisible people, recognized and listened to by diverse cultures that also participate in the so-called holy war. What happens from 1840 onwards, however, is a war motivated by the search for oil —which is anything but holy.

To dominate Palestine, the British tested their, until then, brand new fleet of steamships in the city of Acre, culminating in an unprecedented bombardment with no possibility of response, which reduced the place to ashes. The strategy, from then on, would consist of creating colonies and dividing the land into territories. All of this in a large, knife-shaped territory, where a sea called Dead Sea lies. History books are burned, and it is left to the poets to tell the story. The ongoing genocide in Gaza, starting on October 7, begins by targeting universities and schools. At the beginning of the 20th century, in the state of Acre, Brazil, a centuries-old genocide continued its monstrous course — this time with the cycle of rubber, a demand that arose alongside the automotive industry. The Pano people of the region saw their languages and songs kidnapped, but they recovered them decades later, with the memory technology of ayahuasca. Also in the Amazon region, a few thousand kilometers away, in the state of Para, Emilia reminds us that there is a city called Palestina. The repetition of names does not confuse us.

There is a global network of forces that organizes itself to study the enemy, the origin of its tools and weapons, and to share knowledge. In Brazil, in southern Bahia, the Teia dos Povos, a social movement composed of quilombolas, indigenous peoples, representatives of popular movements and the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra [Landless Rural Workers Movement], the MST, organizes its practice around teachings from Zapatista thought. In recent months, an international flotilla crossed the Mediterranean towards the city of Gaza, but was prevented from landing by the Israeli army.

Another flotilla, this time from the Abya Yala community, carried representatives from sixty indigenous communities and landed at COP30 in Belem, which is not in Palestina, but in Para, while Brazil announces the start of oil exploration at the mouth of the Amazon River. In the midst of all this, the Moon observes everything and influences the tides. From the Favela da Mare in Rio de Janeiro, journalist Gizele Martins, who lives on a street known as Faixa de Gaza, describes the dots that connect the war in her community with the Zionist state of Israel: “(...) fighting for Palestinian life is fighting for black and favela life in Brazil, because lives there and here are lost through the use of the same death technologies produced by the same companies.”

It is October 28, 2025. The government of the state of Rio de Janeiro is carrying out a police operation in the Penha and Alemão complexes, not far from the Sesc Ramos, where “Dibujos de Llegada” is on display. The operation uses armored vehicles and Israeli weaponry — Brazil has become, in the last fifteen years, one of the five largest importers of military technology produced in Israel. This event culminated in the largest police massacre in Brazilian history, with 121 people killed. A gigantic massacre in the midst of the ongoing historical genocide of the black and favela-dwelling people. I'm in Mexico. It is the day of Saint Jude Thaddeus, and the church of Saint Hippolytus is full of worshippers.

I'm told that many mothers, whose children are involved in drug trafficking, are devoted to Saint Jude because of his great power in the face of impossible causes. At the end of the week will be the Day of the Dead, and Mexico City is overflowing with altars and skulls. One of the people who died this week is Lô Borges, a composer from Minas Gerais, who wrote: “If I die, don’t cry, no, it’s just the moon.” Emilia writes to me saying that we have been greenlit to write this text. We understand, as in the vision of Francy Baniwa and Idjahure Terena, that art is a means for the continuation of war. And we know that war is permanent —as the Zapatista Army of National Liberation reminds us.

Another memory from my trip to Palestine is visiting me now. I am in the second-floor gallery of the Walled-Off Hotel in Bethlehem, in the West Bank, facing the labyrinthine Zionist Apartheid wall that divides the region. I am here with a group of colleagues, starting the research for the creation of an artistic residency with Palestinian artists and Huni Kuin, from the Brazilian Acre. Among the works I know is Our Reality, by the Palestinian painter Orjwan Nazzal. In it we observe a world map of black earth, superimposed on a plain green flag background. In the center of the map there is a magnifying glass that enlarges the territory of Palestine. That territory has an eye, which looks back at us. I imagine now that the craters of the Moon must be doing the same, observing our dishonorable wars.

I see many Palestinian flags in Mexico City: in the streets, in universities, in mechanic shops. At the October 2nd march, Palestinian flags were as numerous as, or even more numerous than, Mexican flags. In Oaxaca, I came across a giant purple jaguar with the words "Oaxaca with Palestine" painted on its belly. There is a profound recognition that only peoples who have had their lands stolen can share. At UNAM, filmmaker and researcher Masewal Jesus Flores asks: "How long will we continue to call a “territorial dispute” what is, in truth, a struggle for land?"

Ana Clara Simões Lopes tells me, in a meeting to write this text, that the Moon is not a mirror. Its influence transcends the mere reflection of sunlight. That helps me think of Emilia's work as a piece in the construction of a world without borders. We walk in darkness because we cannot see the lines on the maps, except for those that separate us from the oceans. In her text for the exhibition, the curator writes that, for the artist, the verb to arrive "thus becomes her rejection of the logic of origin and ownership," in drawings that "not only dissolve borders, but also rehearse presences." In this way, Emilia's gaze also opens towards the sky: a presence that observes, from above, a planet without lines drawn within its portions of land. A gaze that trusts the waters.

Scientists are desperately searching for water on the Moon, which is a desert like those in West Asia, a region the British named the Middle East. Perhaps only with water could the Moon be a mirror. However, would we have any desire to see what she would reflect? “Hide me, the moon has come. / If only our mirror were made of stone,” writes Mahmoud Darwish. A stone mirror only reflects the invisible. Emilia's grandmother's passport says very little about her.

It is July 2023. I am saying goodbye to Jerusalem. I am on my way to the Tel Aviv airport while talking with Luai, a taxi driver and travel companion. Born in Palestine and holding a document that allows him to have an Israeli passport, he tells me, throughout our one-hour journey, the stories of his travels around the world. He highlights his experiences in Asia and Africa, but regrets his time in Latin America, when he spent two months in Guatemala. The neighbors of the house he rented, he says, were constantly warning him about the violence in the streets. That made him nervous. “I was born and raised in war, but I don’t know how you can live like this.” Next, Luai tells me about the geological formation of Palestine, starting with the time of Pangaea. He begins by explaining that the Mediterranean, the Sea of Galilee, and the Dead Sea are direct descendants of the Tethys Sea, a Mesozoic formation also known as the Sea of the Tongue, due to its shape. That's when we were stopped at an Israeli checkpoint. They asked for our passports. We remained silent.

Luai owns a haie el zarqa [الهوية الزرقاء], one of the various types of documents that a Palestinian can obtain under the colonial rule of Israel. Having this general record, he must present it as a kind of passport, within his own country, in order to be able to move between the borders that fragment his land —the only city he is not allowed to enter is Gaza. This identity document is also the only one among the local records that allows a Palestinian to obtain a passport —an Israeli one, in this case. His name appears in that passport, but not the name of his country of origin. This is how Luai can travel the world. After a few questions, they returned our documents to us. We continued the journey. Luai's tongue fell silent. This taxi ride is one of the memories that come to mind as I write about the work of Emilia Estrada.

At the center of her first solo exhibition in Rio de Janeiro, “Dibujos de llegada” [Arrival Drawings], curated by Ana Clara Simões Lopes at Sesc Ramos, a drawing imagines the existence of a British Mandate passport in Palestine, which belonged to her grandmother, wrapped in silhouettes of lunar craters. That phantom document reminds us that, of the millions of Palestinians in the world (an imprecise figure), half are in foreign territory.

Granddaughter of that diaspora, the artist traces her trajectory in the visual arts through an open thinking about names, documents, maps and territories. Born in the Argentine city of Cordoba, Emilia is of Palestinian descent and has resided in Rio de Janeiro since 2014. The Palestinian musical collective 47Soul, singing in English, is now making its presence felt: “I don't care where you're from.”

Emilia's transfrontier nature belongs to places marked by land conflicts, all of them related in their wars, all of them continuous nakbas [النكبة], occurring in different timelines of the same coloniality. It is no coincidence that Donald Trump announces a peace agreement in Gaza the same week he bombs ships in the Caribbean Sea. Palestine is not the world. The world is indeed a Palestine with many Gazas, general laboratories of the vulgarization of death. And so, the artist displays nominations: of Latin American cities called Palestine; of fragments of land on the Moon with the names of Arab astronomers from Al-Andalus; of the farces of union and fidelity in the Praça Tiradentes in the center of Rio —which, despite its name, holds in its center an immense statue of Dom Pedro I, carried by indigenous people from different regions of Brazil.

It is December 25, 2024. I spend Christmas at Emilia's house in Rio. On the table there is coffee and halawi [حلاوي] that she herself brought from Ramallah. In the last eighteen months, we have been in Palestine at different times —historic times, even, with an October 7th in the middle. Sharing our experiences with that land is a strange force that unites us. In our sort of fraternal Christmas dinner, we tell stories and try to connect some dots on a global board of conflicts. Brazil remains entangled with the monstrous Temporary Framework Bill, which keeps returning with different cynical faces. Its clear inspiration is the Palestinian Nakba. In his work Carta al viejo mundo [Letter to the Old World], Jaider Esbell writes on one of his paintings: “There is genocide in the Amazon rainforest.” Doesn't the (old) world know? But isn't the world itself a Palestine? The world sees the genocide in Gaza, and? In Salvador, in Bahia —where I live—, there is a periphery called Palestine. From there, Timbalada sings that "Jesus, since childhood, is Palestinian," which could very well mean that Jesus is from Bahia. On this emblematic date, Emilia observes the Moon with a magnifying glass. Maybe she's looking for her grandmother.

While the lights of that December were going out, I had been working on the installation of Louvor à Sombra [Praise to the shadow], present in the exhibition “Forma das Aguas [The shape of water]”, at the Museu de Arte Moderna de Rio, curated by Pablo Lafuente and Raquel Barreto. The lunar surface seems to have become a kind of refuge from which the artist can once again contemplate the blue. A displacement made of coal and gold leaves, to put some colonial concepts on the coffee table, to put them in dialogue, to expose them. What is a territory compared to the power of an Earth? Are there territories on the Moon? Or is the Moon itself a territory? In that case, would the Moon be a moonatory? Emilia observes from the sky. The Palestinian poet Mahmud Darwish writes: “In the dream of the loved one, be the Moon (this is what a woman said to her son at his funeral)”. That night I dream about my grandmother.

That same Moon manifests its profound influence in Dibujos de llegada [Arrival Drawings]. In the work Rumores aridos en rumbos humedos [Arid Rumors in Humid Courses], Emilia seems to create a counter-plane of the Moon and contemplates the surface of the ocean portrayed in the archives of European colonial navigation. The tides are transformed into a mapping, made with a kind of telescope installed on the lunar surface. The artist transforms her gaze into a prayer about the influence of water on a reality that is under a process of transformation. This map of a tide overlaps with that of the City of the Caesars, a mythical city in Patagonia that could never be invaded by the conquerors thanks to the resistance of its original owners. Like the Amazonian Eldorado, the impossibility of mapping it —because it is in another dimension— makes it precisely a point of interest for Emilia.This interplay of opacities and transparencies returns in the series Observação à sombra alta [Observation in the high shadow], in which the artist highlights lunar craters whose Arabic names were given by Western scientists. The names seem to want to give a face, a personality, to those fragments of land. If they had a passport, their name would be printed on it, but not their place of origin. Passports say very little about who their owners really are.

In his essay “The destruction of Palestine is the destruction of the planet”, Andreas Malm recounts the strategies of the British Empire in the 1840s to construct the idea that Palestine was “a land without a people”, “a fertile country, nine-tenths of which lie desolate”. These are accounts taken from diplomatic documents of the time, which reveal the long and slow process of hypnosis that founded Zionism in the region, culminating in the Nakba, more than one hundred years later. When I went to Palestine I found a truly fertile, abundant, and rich land. With cutting-edge research, LGBTQIA+ people, and women in leadership positions. With numerous artists, universities, thinkers, cultural centers, and culture makers. Not by chance, a sacred land also inhabited by many invisible people, recognized and listened to by diverse cultures that also participate in the so-called holy war. What happens from 1840 onwards, however, is a war motivated by the search for oil —which is anything but holy.

To dominate Palestine, the British tested their, until then, brand new fleet of steamships in the city of Acre, culminating in an unprecedented bombardment with no possibility of response, which reduced the place to ashes. The strategy, from then on, would consist of creating colonies and dividing the land into territories. All of this in a large, knife-shaped territory, where a sea called Dead Sea lies. History books are burned, and it is left to the poets to tell the story. The ongoing genocide in Gaza, starting on October 7, begins by targeting universities and schools. At the beginning of the 20th century, in the state of Acre, Brazil, a centuries-old genocide continued its monstrous course — this time with the cycle of rubber, a demand that arose alongside the automotive industry. The Pano people of the region saw their languages and songs kidnapped, but they recovered them decades later, with the memory technology of ayahuasca. Also in the Amazon region, a few thousand kilometers away, in the state of Para, Emilia reminds us that there is a city called Palestina. The repetition of names does not confuse us.

There is a global network of forces that organizes itself to study the enemy, the origin of its tools and weapons, and to share knowledge. In Brazil, in southern Bahia, the Teia dos Povos, a social movement composed of quilombolas, indigenous peoples, representatives of popular movements and the Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra [Landless Rural Workers Movement], the MST, organizes its practice around teachings from Zapatista thought. In recent months, an international flotilla crossed the Mediterranean towards the city of Gaza, but was prevented from landing by the Israeli army.

Another flotilla, this time from the Abya Yala community, carried representatives from sixty indigenous communities and landed at COP30 in Belem, which is not in Palestina, but in Para, while Brazil announces the start of oil exploration at the mouth of the Amazon River. In the midst of all this, the Moon observes everything and influences the tides. From the Favela da Mare in Rio de Janeiro, journalist Gizele Martins, who lives on a street known as Faixa de Gaza, describes the dots that connect the war in her community with the Zionist state of Israel: “(...) fighting for Palestinian life is fighting for black and favela life in Brazil, because lives there and here are lost through the use of the same death technologies produced by the same companies.”

It is October 28, 2025. The government of the state of Rio de Janeiro is carrying out a police operation in the Penha and Alemão complexes, not far from the Sesc Ramos, where “Dibujos de Llegada” is on display. The operation uses armored vehicles and Israeli weaponry — Brazil has become, in the last fifteen years, one of the five largest importers of military technology produced in Israel. This event culminated in the largest police massacre in Brazilian history, with 121 people killed. A gigantic massacre in the midst of the ongoing historical genocide of the black and favela-dwelling people. I'm in Mexico. It is the day of Saint Jude Thaddeus, and the church of Saint Hippolytus is full of worshippers.

I'm told that many mothers, whose children are involved in drug trafficking, are devoted to Saint Jude because of his great power in the face of impossible causes. At the end of the week will be the Day of the Dead, and Mexico City is overflowing with altars and skulls. One of the people who died this week is Lô Borges, a composer from Minas Gerais, who wrote: “If I die, don’t cry, no, it’s just the moon.” Emilia writes to me saying that we have been greenlit to write this text. We understand, as in the vision of Francy Baniwa and Idjahure Terena, that art is a means for the continuation of war. And we know that war is permanent —as the Zapatista Army of National Liberation reminds us.

Another memory from my trip to Palestine is visiting me now. I am in the second-floor gallery of the Walled-Off Hotel in Bethlehem, in the West Bank, facing the labyrinthine Zionist Apartheid wall that divides the region. I am here with a group of colleagues, starting the research for the creation of an artistic residency with Palestinian artists and Huni Kuin, from the Brazilian Acre. Among the works I know is Our Reality, by the Palestinian painter Orjwan Nazzal. In it we observe a world map of black earth, superimposed on a plain green flag background. In the center of the map there is a magnifying glass that enlarges the territory of Palestine. That territory has an eye, which looks back at us. I imagine now that the craters of the Moon must be doing the same, observing our dishonorable wars.

I see many Palestinian flags in Mexico City: in the streets, in universities, in mechanic shops. At the October 2nd march, Palestinian flags were as numerous as, or even more numerous than, Mexican flags. In Oaxaca, I came across a giant purple jaguar with the words "Oaxaca with Palestine" painted on its belly. There is a profound recognition that only peoples who have had their lands stolen can share. At UNAM, filmmaker and researcher Masewal Jesus Flores asks: "How long will we continue to call a “territorial dispute” what is, in truth, a struggle for land?"

Ana Clara Simões Lopes tells me, in a meeting to write this text, that the Moon is not a mirror. Its influence transcends the mere reflection of sunlight. That helps me think of Emilia's work as a piece in the construction of a world without borders. We walk in darkness because we cannot see the lines on the maps, except for those that separate us from the oceans. In her text for the exhibition, the curator writes that, for the artist, the verb to arrive "thus becomes her rejection of the logic of origin and ownership," in drawings that "not only dissolve borders, but also rehearse presences." In this way, Emilia's gaze also opens towards the sky: a presence that observes, from above, a planet without lines drawn within its portions of land. A gaze that trusts the waters.

Scientists are desperately searching for water on the Moon, which is a desert like those in West Asia, a region the British named the Middle East. Perhaps only with water could the Moon be a mirror. However, would we have any desire to see what she would reflect? “Hide me, the moon has come. / If only our mirror were made of stone,” writes Mahmoud Darwish. A stone mirror only reflects the invisible. Emilia's grandmother's passport says very little about her.